A number of people have observed that the current Coronavirus crisis has the potential to begin new trends, and accelerate pre-existing ones.

Trends like the global decline in CO2 emissions over the last few months, which many (myself included) hope will carry over into the post-Covid era.

Or the shift to collaborative working thanks to the growth of tools like Slack, on which we now spend an average of one billion minutes each weekday. Their CEO, Stewart Butterfield, summed it up powerfully: “It felt like the shift which we believed to be inevitable over 5–7 years just got fast-forwarded by 18 months.”

Well, another trend I think we’ll see hastened is the move to a self-serve customer support model – along with our increasing lack of patience for those brands unable to deliver it. Particularly in sectors, like financial services, that have traditionally lagged behind.

Buying things is hard

As we all know first-hand, it’s harder than ever to be a consumer right now. (The more socially conscious among us will say this is another positive trend.)

The process of buying stuff is more difficult, not only because there’s less of it about, but because it’s tougher for it to physically get to you. And if you’ve already bought something and need some help, well, it’s harder to get hold of whoever sold it to you, too.

A phone call to Sky right now will yield a recorded message telling you to hang up unless you’re a key worker.

Call your bank or credit card and they’ll likely hit you with a comparable message, suggesting that, due to abnormally high call volumes, it might be worth trying again tomorrow (…as if it’s likely to be any different then.)

British Gas has gone even further. You don’t even have to call them to be told they don’t want to speak to you. Listening to the radio last week I was struck by its latest ad, pleading with me not to call them unless it really is a ‘come quick, my boiler is smoking and making angry noises’ style emergency.

Just stop and think about that for a moment. A company is spending its media budget on ads to tell everybody – customers, prospects, literally anyone who’ll listen – not to interact with them.

Now, of course, I get why. These companies will be overrun with calls, and it’s only right and natural that they triage them so as to focus on the queries – and the customers – that are the highest priority.

But it’s no less frustrating. And the reason it’s so frustrating is because I don’t want to call them in the first place.

Take my phone call to Sky. I had wanted to buy a film. (Yes, I’m ashamed to say I’ve burned through all of Netflix. And yes, I’ve re-watched all the Star Wars films. No, not Episode I. Don’t be silly, I’m not that desperate). But for some annoying reason my subscription hasn’t been set up for purchases.

On trying to resolve this issue, my TV box told me to give them a call. Only for my phone to tell me to go away. It all makes for an infinite loop of dashed hopes and mounting anger, when all I want to do is hand over my money. Will someone please take my money?!

A disjointed customer experience

The current situation has thrown into even greater stark relief the friction-laden obstacle course that many brands have created for those looking to buy or find support.

And it’s shown just how far behind the curve some sectors are. Particularly utilities and financial services. You know, just the small ones, that no-one need use.

Established players within these sectors suffer from ingrained operational inefficiency. Product, marketing, sales and post-sale support are seemingly siloed, with little to no consistency or communication; while their technology stack will no doubt consist of various legacy systems imperfectly patched together.

As a result, the easiest option for these businesses is to throw people at the problem. Build big teams of long-suffering customer operations folk, and ask your customers to call them.

A structure like this simply adds cost and inconvenience, and, when it gets put under serious strain like it is today, starts to crumble.

It’s led to legacy brands frantically trying to push their customers to fend for themselves, but without having put in the groundwork to let them do so effectively.

The changing face of customer success

Now you might say, ‘hang on, lots of people prefer to pick up the phone’. And, you’d be right. According to Hubspot, 30% of people would choose to call a company to resolve an issue or answer a question.

But I have a feeling that’s down to the paucity of other, more convenient options – not to mention a consumer habit that’s been reinforced by the phone-first approach of larger brands. And it’s already starting to break down.

Research by Forrester conducted a few years back has shown that the tide is turning, with online channels – particularly knowledge-bases – beginning to overtake the phone call in the popularity stakes.

Ultimately, I’d suggest that customers are intuitively channel agnostic. People don’t think in those terms. They just want to fix their problem in the fastest, simplest and most convenient way. And more often than not that probably means sorting it yourself, within the very product that you’re using.

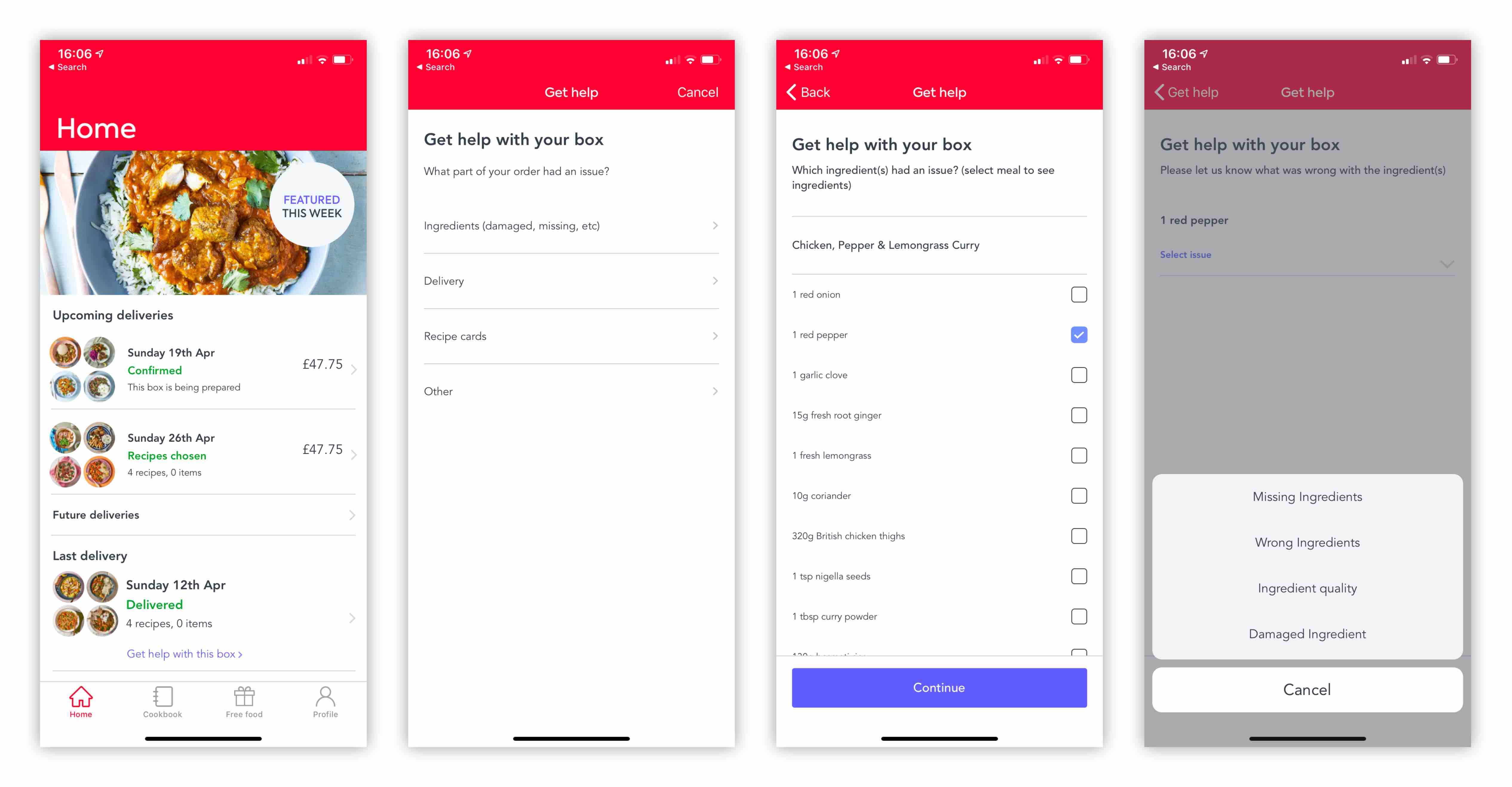

Take Gousto – my lockdown saviour – as an example. If lurking among the fresh veg is a less than fresh pepper, they don’t force you to call them. Who wants to call anyone for a pepper. Instead, they use their product to help you report and fix it straight away (in this case with a refund).

This is not rocket science. Modern, digital-first brands get it. They understand that convenience rules – and that a digital solution doesn’t have to be devoid of delight.

The future should be friction free

It’s no surprise, then, that the brands that have proven most successful over the last decade are those that have sought to remove friction from the customer journey.

It’s no surprise, either, that these brands – the Amazons, Ubers, Slacks, Zooms, Deliveroos and Goustos of the world – are proving especially helpful during the current crisis.

They have removed friction within their technology – using APIs to seamlessly connect micro-services to create rich, rounded experiences.

They have removed friction within their products – with intuitive, low-click journeys and well-crafted content that minimises clunk, maximises speed, and anticipates questions or problems before they arise.

They have removed friction within their customer operations – helping customers to help themselves through in-app customer support and online problem-solving content.

And they have removed friction within distribution, too – making it super easy to buy once, buy again and refer others.

Now, there have been few global events that have so universally and thoroughly changed human behaviour as that of the last few months – and only time will tell how permanent these changes will be.

But just as I hope it propels us to protect our planet and work more effectively as teams, I also hope it can usher in the end of some really naff customer experiences.

Thankfully, in a world where 84% of us have left a brand because of poor service, I reckon we stand a good chance.