Building great products that solve real customer problems is hard. Doing it efficiently is harder still. And doing both as a small team – where you’re short on team-members and long on tasks – well, that’s where it becomes really challenging. But, as the saying goes, if it was easy, everyone would do it!

I joined around six months ago as Seccl’s Head of Product, and one of the first things that struck me about the company was its culture of openness, coupled with a genuine desire to continuously improve – and a healthy dose of pragmatism.

It’s exactly those traits that mean we’re always looking to improve how we build, as well as what.

And so in this, the first of what’ll hopefully be many blogs devoted to exploring our product development process, I thought I’d explain how we go about planning and prioritising our work here at Seccl – and talk through some of the experiments we’ve recently been running.

Learning from Basecamp

It’s a simple principle of software planning that you can fix the scope, or you can fix the time – but you can’t fix both.

Sure, you can pretend otherwise if you want. But universal rules always have a way of winning out, and at some point you’ll be forced to choose: either cut the scope, or give yourself more time to deliver it.

It was as we grappled with this unchanging principle, while planning our teams’ workload, that Adrian (our Head of Engineering) and I thought we’d try something new to improve the predictability of our delivery here at Seccl.

We’d both read ‘Shape Up’ by Basecamp and been impressed by their approach, so we thought we’d run an experiment and trial some of their methods. Here’s how it works…

Cycles

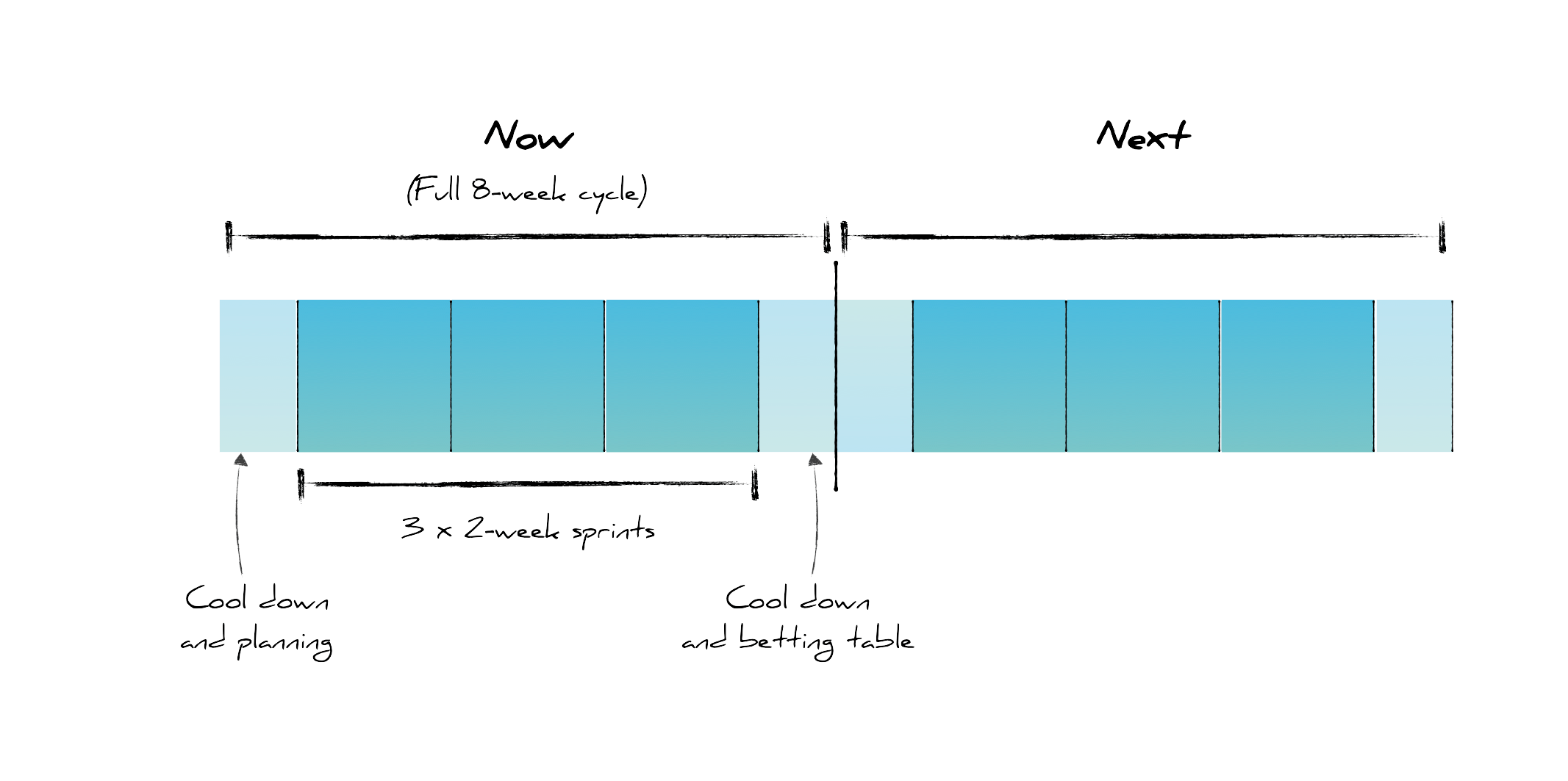

We now operate in eight-week cycles that are made up of three two-week development sprints, followed by a cool down sprint. The eight-week planning window allows us to work at a granularity of output more useful for management than a two-week sprint. The idea being that, while you probably can’t build something that genuinely moves the needle in a single sprint, you certainly can in three.

Cool down

The cool down is super important. It provides time for the development team to work on stuff like refactoring, updates, and minimising tech debt. It’s also where we do a lot of our deeper planning workshops for the next cycle.

This stuff might not sound sexy, but it’s super important – and start-ups looking to scale ignore it at their peril. After all, it’s called tech debt for a reason: the longer you leave it, the more interest you pay – in our case in the form of lost efficiency and future development challenges.

Betting

Just like at Basecamp, we use the language of ‘bets’ to describe a commitment to build something. We find it helps us place the decisions we’re making about product development in the context of the business.

After all, we’re investing the company’s resources to try and create a financial payoff. No matter how much you plan, it’s a course of action that involves unknowns and risks. It is, in no uncertain terms, a bet.

Thinking in terms of betting a stake helps to reframe the conversation from ‘how much feature work can we stuff into this cycle’ to ‘how can we de-risk the next eight weeks?’. The prospect of creating short feedback loops, instead of big bang feature releases, suddenly makes a lot more sense.

We make our bets at a session called the betting table, in the last week of our eight-week cycle.

Our eight-week development cycle, made up of three two-week sprints, and another two-weeks of cool down

Appetite

We timebox our bets. As a business, we set an ‘appetite’ for delivering a customer outcome, which is represented in the number of sprints we want to commit to delivering it: either one, two or the full three that are available to us in a cycle.

Rather than asking ‘how long will the feature take to build’, we think of it the other way and ask ‘in the current context of our business, how much is it worth to us to solve this customer’s problem?’

Note, we avoid the word ‘feature’ deliberately, as it’s loaded with the idea of a solution already in mind (a fixed scope). Instead, we commit to solving a customer problem. As to what the solution looks like – its breadth, depth and approach – that can vary.

And this isn’t just about the product and engineering teams. Sure, we’ll commit to deliver a solution to said customer problem by the end of the cycle – but it’s two-way. The business is undertaking not to change its priorities, too (and thereby ‘change the odds’, as it were).

Shaping

Shaping is the process we go through before making a bet. The product team spends time speaking to customers, looking at data, and gaining a deep understanding of the problem that they’re hoping to solve.

We look at possible solutions at a high level – the ‘goldilocks amount of detail’ as Basecamp call it – and spend just as much time defining what we’re not doing, and identifying the unknowns or potential rabbit holes that could distract us.

The process is hugely important in helping the business to make informed decisions, by allowing them to understand exactly what they’re betting on, and the outcome it will (and won’t) achieve. And it also then gives the engineering team a high-level brief that defines what success looks like.

So, what have we learned?

We listen more effectively

Spending deliberate time shaping has helped to uncover some great insights that might otherwise have been lost.

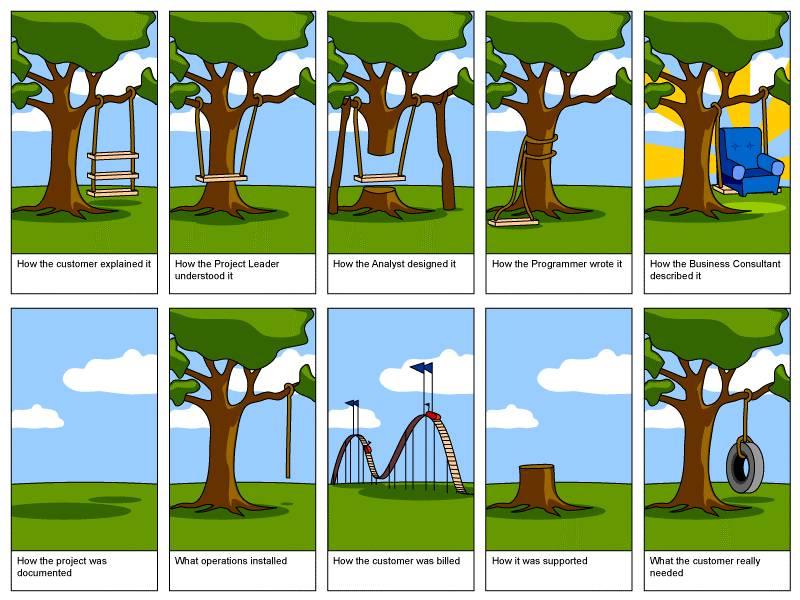

Every conversation we now have with our customers focuses on ‘why’. We try to get to the heart of the problem they’re trying to solve, rather than jumping to fix it – which opens up the range of possible solutions. Sometimes the feature we think they want might not be what they need.

More effective shaping helps avoid wasting time building the wrong things...

Appetite improves problem-solving

By constraining the proposed solution to a given appetite, it means we’re not working off a blank canvas.

In one particular example, we were given a small appetite by the business for what was originally considered a ‘big piece of work’. This forced us to look at our options, and creatively problem-solve to find a solution to match the appetite.

Flexible scope can be hard in regulated environments

The ‘time is fixed, scope is variable’ concept is a great one to live by – and in most cases works really well for us.

But it can make life difficult when working on items that are specified by the regulator. Working within the investments and advice space involves meeting certain regulatory obligations, which means that the scope for certain projects is non-negotiable – and by definition a priority.

Is it a massive problem? No. It just means we sometimes have less flexibility; and in any case it’s something we’ll have to learn to manage.

Looking ahead

I’m a huge believer in stealing people’s great ideas (in an open and above-board way, of course!), before evolving and merging them with others to fit our specific context.

Basecamp’s Shape Up provided an amazing template for us, and we’re already evolving it to make it our own.

And that evolution will be constant. Like products themselves, the process of developing them is never something you truly ‘finish’ – and we’ll always be experimenting with new ways to make it better.

One of the things we are looking at now is how we can merge the best bits of the Google Ventures design sprint into the process.

Watch this space: we’ll let you know how it goes!